On Violence

I have to write an essay on settler colonialism today. In the week of the Bondi massacre it is tough.

A while back I worked with an outback-based teacher and my university (which the help of dozens of generous donors) to bring a group of Barkandji kids from the outback town of Wilcannia to visit Sydney. I tagged along on one of their days, visiting a rugby league centre and Sydney’s iconic Bondi beach. Their teacher and I were still on Bondi’s cafe-lined street when the kids - who we intended to meet on the beach - were already back from seeing what one young fella called ‘the river’ (a geographical touchstone - ‘Barkandji’ means people of the river, after the river Barka that defines their country). What happened? I asked. An affronted young woman looked at me wide eyed and in that beautiful, lilting-to-the-point-of-melodrama Barkandji accent said ‘I don’t want to see all them people with no clothes on’.1

This week Bondi beach was the site of a massacre.

Two men, a father and his adult son, shot and killed or injured dozens of people, mainly of Jewish faith during a precious religious event.

I saw via social media that it was happening on Sunday night and watched with horror the phone-filmed footage of the place that I, like many Australians, feel deeply - my father grew up in Bondi and as a kid we visited the beach a lot, as I have done often since. The disjuncture of the scene with other knowledge was dislocating. The scene comes with feeling of hot sand between toes, ticklish grass beneath those palm trees linked inexorably to the thrilling chill of ice cream. Anticipating the sting of salt water on slightly sunburned skin while running over that exact bridge.

It seemed - and seems - beyond belief. With horrors now compounded by everyone pointing accusing fingers at groups that are not the international terrorist organisation actually to blame, but who they already did not like. Immigrants. The Prime Minister. Peace marches for Gaza. The word ‘Islamaphobia’. It is toxic, and spreading. The UK’s solution is to ban a slogan akin to vive la révolution, either reflecting an unseemly misunderstanding of global geopolitics, or else going still further than they already have to demonstrate that Labour not only will inhibit democratic protest, but is really no longer even close to being politically Left.

Settler Capitalist Violence

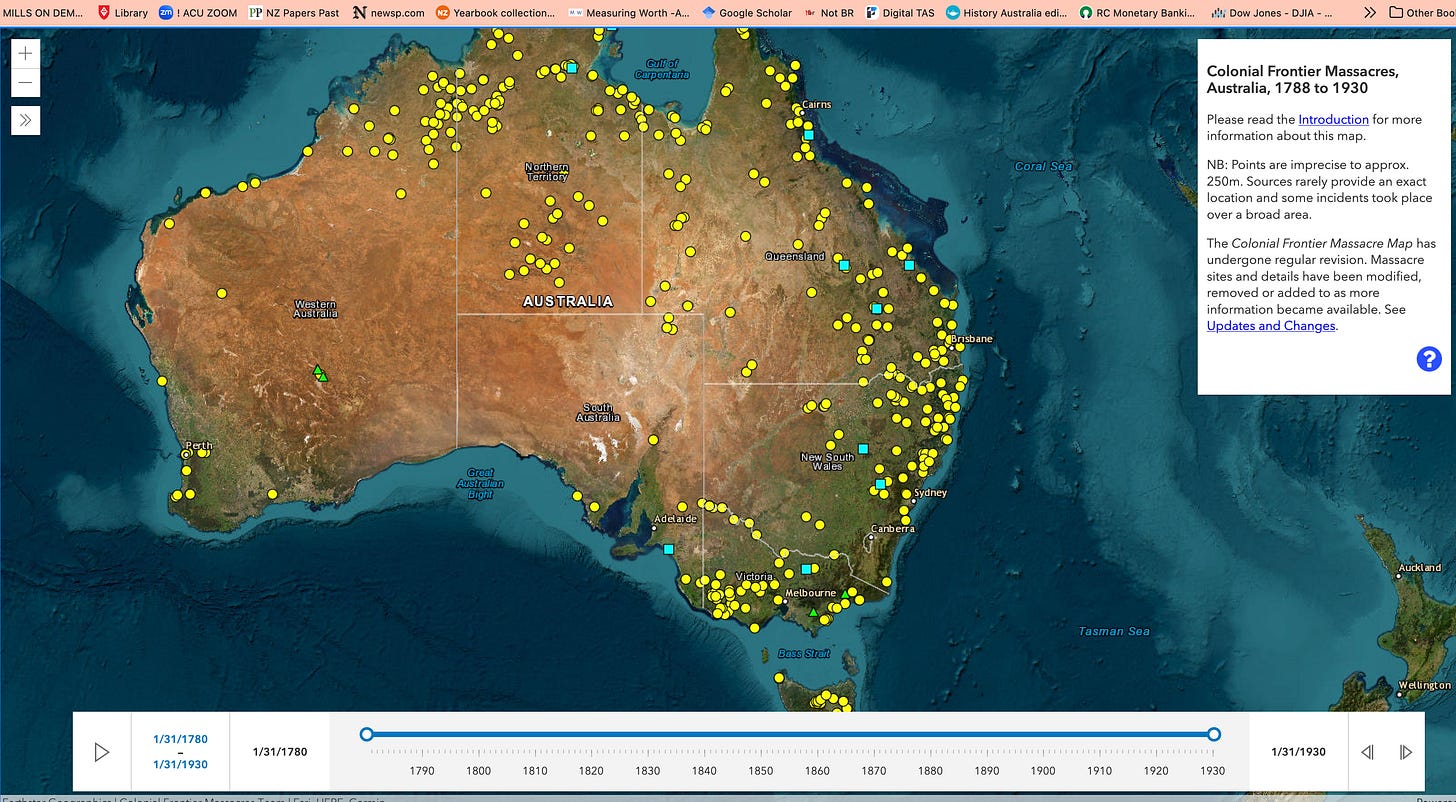

We are shocked. And yet, the settler colonialism that made and structured Australia as elsewhere has been defined by violence. As the late historian Lyndall Ryan worked so hard to demonstrate, the continent I love is dotted with massacre sites. The trauma that was and is inflicted by massacres and other forms of settler-colonial violence (and if any regime has been remarkably creative in its application of violence it is settler colonialism) shaped the young Barkandji children who refused Bondi beach as it does and will all others who have been forced to experience such horrors.

Today my task is to finish a review essay on four books that examine exactly this.2 One is Tyler A Shipley’s Canada In The World: Settler Capitalism and the Colonial Imagination, which shows the continuity of the logics of of colonial relations with First Nations people up to the present far-right, including anti-immigration neo-Nazis and anti-semitic terrorists. Another is Hamish Maxwell-Stewart and Michael Quinlan’s Unfree Workers, reminding us that getting labour for settler colonies was such a problem for capital, that unspeakable levels of violence and unfreedom were inflicted to force people to do the work. Malcolm Harris’s Palo Alto, which links the growth of a military-industrial complex in California to Silicon Valley, the perverse effects of deeply intensive human capital investment alongside widening inequality and deepening poverty and the key beneficiaries - American finance. Finance is also the centre of Catherine Comyn’s Financial Colonisation of Aotearoa, which demonstrates that the entire settler colonial project was grounded in financial speculation.

The violence is unbearable, the political fragmentation - the absence of solidarity in opposition to the structures that lie at the heart of the violence - is heartbreaking.

And yet, as all these authors show, resistance is ever-present in many forms, even (as Maxwell-Stewart and Quinlan show) for those most surveilled workers: prisoners of the British Empire. In his trademark bleakness, Malcolm Harris even positions California’s suicide rate as a sort of resistance to the ‘Palo Alto system’ that robs the middle class of their selfhood and the poor of everything else.

F*cking capitalism.

My favourite, however, is Te Peeke o Aotearoa, a Māori bank, or treasury of the Kīngitanga, the Kingdom that Māori groups (iwi) established together to embody sovereignty and engage on equal terms with Empire. By this bank and the banknotes it issued, Catherine Comyn shows that Māori people sought - and took - control of the systems of credit, taxation and investment (including investment in political effort) that had systematically robbed them of their land, turning them instead to their collective political interests.

In order to write the essay I must now leave this blog to draft, I have been reading Hannah Arendt’s famous essay On Violence. It reflects such an interesting moment in the Old-New Left moment - and it lacks much. But I found her reflections on p.56 important:

To sum up: politically speaking, it is insufficient to say that power and violence are not the same. Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent. Violence appears where power is in jeopardy, but left to its own course it ends in power’s disappearance.

This helps explain the ever-presence of violence in settler colonialism. The system knows - insofar as a system can know - that it lacks legitimacy. It deploys violence in the absence of authentic power.

To me that suggests that it cannot ultimately succeed. In the meantime, however, the violence is unbearable.

Love and solidarity x.

Probably most people were wearing swimwear, but I never made it down there that day, so I can’t say for sure. I’m sure there was indeed a lot of visible human flesh.

By Christmas Julie McIntyre, I promise.